The Night Disco Died | The Racist & Homophobic "End" to Disco

Imagine: it’s the summer of 1979, the weather sticky and hot, the radio airwaves buzzing with the funky basslines and sultry voices of disco powerhouses like Donna Summer, the decided “Queen of Disco,” Earth Wind & Fire, Gloria Gaynor, and The Village People…The world seems to be consumed in a disco craze; my own mother, born in 1971, recalls skating at the roller rink to disco as a child wearing bedazzled bell bottoms.

Despite most of mainstream America finding itself in the midst of a disco obsession, an anti-disco riot, coined “Disco Demolition Night,” by primarily white Americans breaks out on the night of July 12, 1979 at a Chicago White Sox baseball game, causing the second-ever forfeit in MLB history and the decided death of disco.

The Birth of Disco

Disco found its roots in nightclubs that opened up in New York City and Philadelphia during the mid and late sixties. At the same time, the “Philly soul” sound soared in popularity following the release of Jerry Butler’s 1968 hit “Only the Strong Survive”; this exact Philly sound became the blueprint for disco music in the coming years. Philadelphia soul, Phillysound, or TSOP pulls from soul and funk, featuring lush musical arrangements, soaring strings, a strong backbeat, and a dream-like quality to the sound. For musical reference, listen to the entire discography of MFSB, “Philadelphia Freedom” by Elton John, and “Ooh Child” by Dee Dee Sharp.

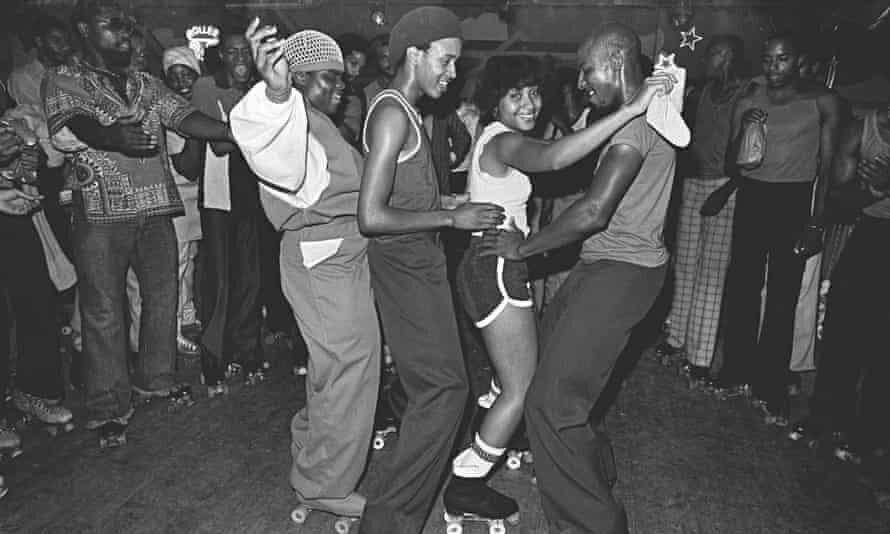

Folks dancing at Brooklyn’s Empire Roller Disco in 1979 (via The Guardian)

These early disco clubs attracted and welcomed those who did not fit in with mainstream American WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestant) culture: folks of color and LGBTQ+ folks who were often turned away from white clubs.

Liberated by the Stonewall demonstrations of 1969, LGBTQ+ folks flocked these clubs that allowed them to be their truest selves, embracing disco as not only a facet of Black culture, but as gay culture as well. And the singers and faces of disco music? Black and Brown folks in colorful, expressive, and flamboyant clothing, makeup, and hairstyles. Themes of joy, free love, passion, sex, lust, and admiration prominent in disco coupled with the Black and Brown faces of the genre provided young BIPOC (Black Indigenous People of Color) with positive and liberating messages and people like them to look to.

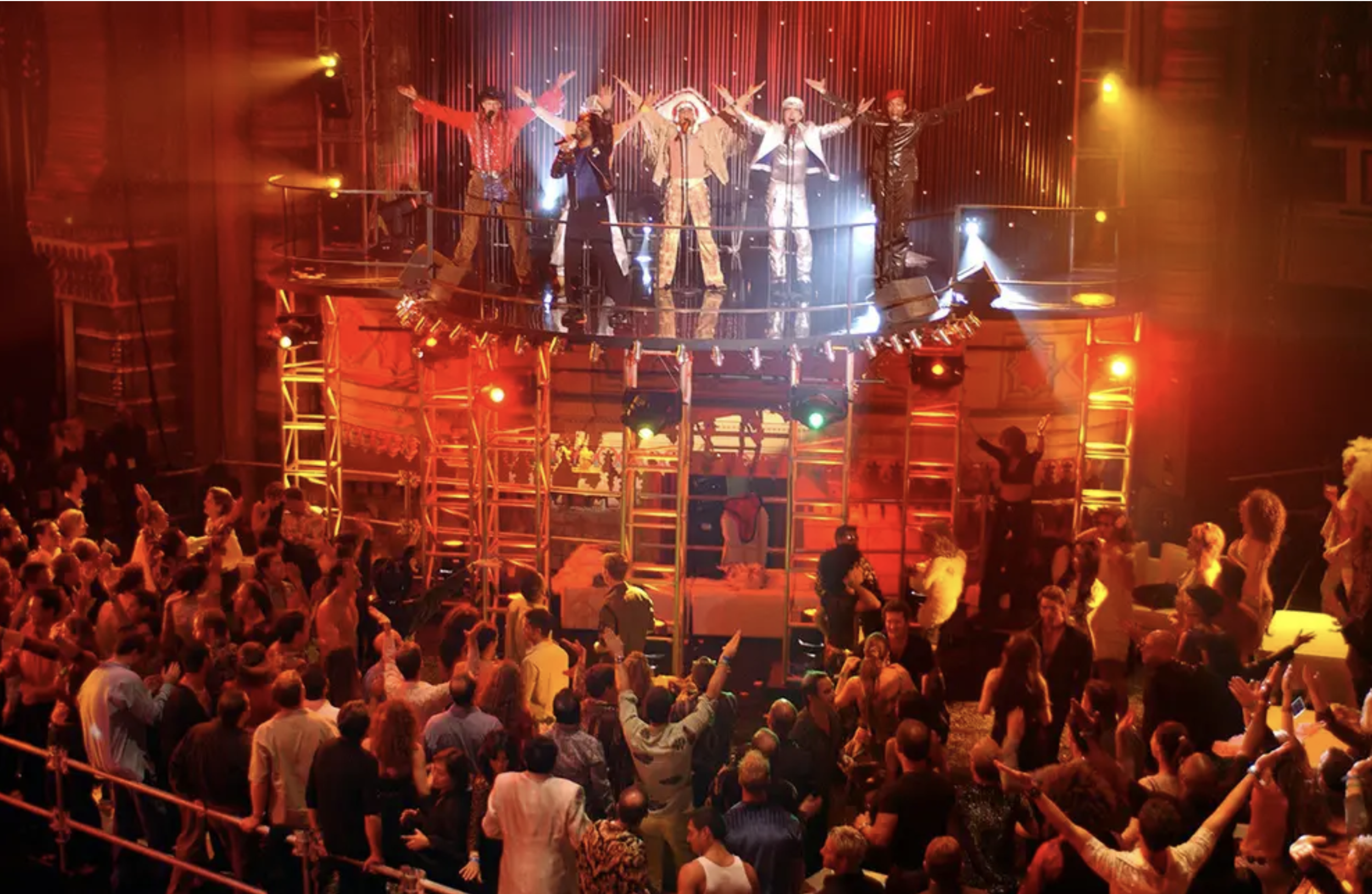

The Village People Performing at the Shrine Auditorium in 1970 (Via Amanda Edwards / Redferns / Getty Images)

Disco’s Popularity

In 1971, the iconic television show, Soul Train, aired on national TV for the first time (it had been a local favorite of Black Chicago natives starting in 1970), becoming an instant hit with Black folks around the country. Soul Train complimented disco’s morals and amplifying abilities, as it also depicted Black people in a positive light: all sleek styles and healthy Afros, talented amateur dancers, incredible performers, all lead by the smooth-talking host, Don Cornelius, who initially pitched the show as “the American Bandstand of color.” The popularity of the show also meant more white people being introduced to A. a more positive depiction of Black folks in mainstream media, and B. Disco music, fashion, and culture.

**Brb, taking style tip notes from this video**

Between the years of 1974 and 1977, more and more white Americans became obsessed with disco.

Even devout rock ‘n’ roll radio stations converted to being disco-only. In 1977, America’s love of disco culminated in the film Saturday Night Fever, based on an article written by British journalist Nik Cohn about New York City’s disco culture. The movie stars John Travolta as Tony Manero, a sexually promiscuous, hot-headed, and somewhat vain young Italian-American paint store clerk in Brooklyn who lives to be able to dance at disco clubs with his friends on the weekends. Numerous movie critics called the film the best movie of 1977, evident in its nomination for numerous Golden Globes including Best Motion Picture. Funnily enough, Fever’s cast of characters is the antithesis of the disco scene: they’re chauvinistic, homophobic, and racist. And, unsurprisingly, Cohn later admitted to fabricating the article about NYC’s disco culture and to knowing very little about the culture itself, meaning the celebrated film is based on a lie. Nevertheless, white folks ATE. IT. UP!

Journalists of the mid-to-late seventies had a hard time explaining the U.S.’ infatuation with disco music, according to Dr. Gillian Frank, Historian of Sexuality Princeton University, especially when considering the genre’s creation by the subculture of white America. Rock ‘n’ roll, for example, was created by Black songstress Sister Rosetta Tharpe. Why didn’t white folks have an issue with this genre? Well, it was stolen and popularized by white rock ‘n’ rollers like Elvis Presley and The Beatles.

Disco’s popularity marks one of the first instances in American history since jazz in which a music genre created and popularized by Black artists goes mainstream and still remains Black. Sure, The Beegees and ABBA created countless disco hits that folks continue to dance to today, but the genre was undeniably dominated by Black and Brown artists.

The Death of Disco

So, how did America go from disco-obsessed to disco-hating seemingly overnight?

Many point to Chicago radio DJ Steve Dahl as the man behind disco’s demise. Dahl, then 24-years old, got fired from his job as a DJ for WDAI Chicago on December 24, 1978 after the station decided to make the switch from rock to disco and cut his morning show. Dahl was angry, but instead of turning his anger onto his former bosses or the radio station itself, Dahl was angry at disco.

Dahl would be rehired at The Loop radio station, a rival station to WDAI, and would lead an anti-disco crusade. He took to destroying disco records on his morning show: “Back in the day when we had turntables, I would drag the needle across the record and blow it up with a sound effect, and people liked that.” Dahl constantly mocked disco on-air, and even released a song parodying Rod Stewart’s hit “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy?” called “Do You Think I’m Disco” (for the sake of your ears, don’t look this song up). Dahl’s antics grabbed the attention of talk shows that invited him on.

““It’s not so much the music that I dislike, it’s actually the culture,” ”

“it’s actually quite intimidating to our audience, to myself, to most rock ‘n’ rollers because you have to look perfect, your hair has to be beautiful.” Later in the interview, Snyder and Dahl joke about writers blowing the popularity of disco out of the water because of their supposed love for going to Studio 54 (a popular club at the time) and “put[ting] on a dress.”

Steve Dahl cleverly masked any anger towards disco culture behind a front of teasing and triviality, breaking brand-new records against his head to choruses of laughter: “Well, the first thing that I have against [disco] is that I can never find a white three-piece suit that fits me off the rack.” In his book Disco Demolition, Dahl says he saw disco as phony and inauthentic and abhorred having to “make room for the disco format” after being fired. Dahl’s wife Janet remembered her husband’s actions as wanting to be accepted and validated, echoed by his fans feeling “lost in a new culture of women’s liberation, Black rights, sexual liberation, and Studio 54-inspired androgyny and materialism.” Funnily enough, disco was created by and for folks who felt the same disregard by white rock ‘n’ roll culture.

Despite his claims that his anti-disco movement was a harmless stunt, Dahl’s dress in army fatigues and a military-style helmet and his proclaimed anti-disco army of followers, the Insane Coho Lips, lends some sort of seriousness to his hatred of disco. What may have been a funny joke between Dahl and his friend emboldened young white Americans to hate disco because of its popularity with and uplifting of LGBTQ+ folks and/or BIPOC. On the topic of the Insane Coho Lips and Dahl’s impact, Tom Joyner, a Black radio DJ, said “I’ve known some people that walk down the street with something on their shirts or on the back of their jackets that says ‘disco,’ and some of his, what do you call, “Dahl’s army” or whatever they are, they almost got jumped on. [Dahl] could very well be a dangerous person.” This is evidence to the ability of Dahl’s rhetoric to be taken as racist and homophobic by his followers.

Disco Demolition Night

Soon enough, Steve Dahl’s radio show caught the attention of Mike Veeck. Veeck’s father, Bill, owned the Chicago White Sox at the time and held all sorts of crazy promotions at the games to encourage ticket sales. Bill Veeck invited Dahl to host a “Disco Demolition Night” on July 12th during a double-header game to promote ticket sales—anyone who brought a disco record to be blown up by Dahl with them would only pay 98 cents for entry. Andy Lansing, a witness to Disco Demolition Night, remembers free haircuts and a shower installed in the outfield of Comiskey Park: “it couldn’t have been more outrageous, but it was really fun.”

Jim Maines, a white witness to the riot, remembers a rowdy crowd using disco records as Frisbees. Vince Lawrence, on the other hand, was a Black usher and aspiring musician and he hoped to be able to take a few disco records home with him. Lawrence recalls being one of the only Black folks out of the 50,000 people who attended that game. Lawrence also recalls the types of records that were brought to Comiskey Park: “Tyrone Davis records, friggin' Curtis Mayfield records and Otis Clay records, records that were clearly not disco,” but music by Black people.

Dahl, holding his helmet, surrounded by Chicagoans on Disco Demolition Day (Via The Economist)

As the first game ended, Dahl, dressed in military gear, took centerfield and began to fire up the crowd on the mic: “these disco records that you brought tonight, we got ‘em in a giant box, and we’re gonna blow ‘em up real good” *cheers*. And that’s what they did, to a chant of “disco sucks,” leaving a crater in centerfield. The White Sox began to warm up for the second game as fans continued to cheer and rave when, suddenly, hordes of people rushed the field, stealing bases, sliding down the foul poles, attempting to break into clubhouses, and lighting fires. Sox player Steve Trout remembers almost being hit by a The Village People record that came careening from the stands, lodging into the grass near his right foot, and player Ed Farmer got into a fistfight in the parking lot. Vince Lawrence recalls a stranger running up to him, breaking a disco record in his face, and screaming “Disco sucks! Ya see that?,” as if he were a physical representation of disco. Unsurprisingly, the White Sox were forced to forfeit the game.

The chaos descended into a full-blown riot, ending with 39 people arrested and a once-raging bonfire smoldering in the grass. Even Andy Lansing, one of the white witnesses, remembers the event not feeling “completely safe.” The riot would be celebrated 40 years later during pride month of 2019, with Steve Dahl throwing the first pitch at a White Sox game and 10,000 commemorative “Disco Demolition Night” t-shirts being given away.

The Disco Demolition Night Riot, July 12, 1979 (Via Musicorigins.org)

Today’s Reflection

Dahl and defenders of the anti-disco movement continue to label the riot as harmless and the movement itself as simply coming to the defense of the genre of rock ‘n’ roll and its listeners who felt they did not belong in the world of disco. Dahl calls for viewing this movement through a 1979 lens, but even then, witnesses of the riot understood its racist and homophobic undertones. “Your most paranoid fantasy about where the ethnic cleansing of the rock radio could ultimately lead… White males, eighteen to thirty-four are the most likely to see Disco as the product of homosexuals, blacks and Latins, and therefore they’re the most likely to respond to appeals to wipe out such threats to their security,” said Rolling Stone music critic Dave Marsh, an attendee of the Disco Demolition Night promotion. Dahl’s claims of feeling too uncomfortable to don disco garb and “blowdry his hair” are, I think, veiled attempts at disguising his and other rockers’ intolerance and fear of non-white culture.

Dahl asserts that he “didn’t know what he was tapping into,” but that his anti-disco crusade “obviously threatened a certain group of rockers.” When that group of threatened rockers is all-white and all-male, an anti-disco riot then becomes anti-queer, anti-Black, anti-women. And that is inexcusable. Nile Rodgers of the legendary funk group Chic later said the event “felt to us like a Nazi book-burning. This is America, the home of jazz and rock and people were now afraid even to say the word 'disco'. I remember thinking—we're not even a disco group.” Blowing up tons of Black and queer art in an organized fashion certainly emulates a book burning in my eyes.

Seemingly overnight, America had turned its back on disco.

Newspapers and magazines talked about disco culture being on the decline and all-disco radio stations reverted back to rock ‘n’ roll. In actuality, disco was still being listened to and played by the mainstream, but it was being marketed as “dance music.” Over the next two decades, disco music would evolve into house music and techno through the genius of Black artists in, gasp guess where, Chicago (and Detroit). And white audiences would eat up that genre too (and claim that David Guetta invented it, but I digress).

Ocala Star-Banner newspaper : “Anti-Discomania: Studio 54 Won’t Make It To Sox Park” (Via I.pinimg)

On the heels of Pride Month and beyond, it is important that folks remember disco’s end in the context that’s been there since 1979: an end due to homophobia and racism. It’s also even more important to remember its origin and impact.

To many, Disco Demolition Night served as a catalyst to the end of a fad. To perhaps many more, disco was seeing themselves in the mainstream, or a chance to be themselves, or a creative outlet, or all three. To me, disco represents a sweet spot in American history when Black and Brown folks and LGBTQ+ folks, folks like me, were not forced to live in the shadows of the mainstream. I can only imagine the pure joy that young gays felt dancing to “I Was Born This Way” by Carl Bean. Disco promoted a flamboyant, free-spirited lifestyle, and an escape for those to whom being flamboyant and free-spirited meant opening yourself up to harm. Disco is and will continue to be celebrated by the folks who created it and needed it.

Happy Belated Pride Month!

A man blowing a whistle in a sparkling purple outfit dances at Studio 54, 1979 (Via Waring Abbott / Getty Images)

The Queen of Disco Donna Summer performs onstage in a feather costume, circa 1976 (Via Michael Ochs Archives / Getty Images)